It's All Connected: Unearthing the Potential in Hidden Collaborative Networks

This article was co-authored by i4cp Thought Leader Consortium members John Boudreau and Rob Cross. It was originally published on Visier .

Lois Weisberg, Chicago’s commissioner for cultural affairs from 1989 to 2011, passed away at age 90 in January 2016. She was made famous in part by Malcolm Gladwell, author of the book “The Tipping Point,” who described her as the quintessential “connector.”

Her connections included Tony Bennett, Allen Ginsberg, Arthur C. Clarke, as well as doctors, lawyers, environmentalists, real estate moguls, politicians, activists and street peddlers, according to her obituary in the New York Times.

Does your organization have such “connectors?” If you do, they are likely invisible to your traditional HR systems–just like Lois Weisberg, who few people had heard of until Malcolm Gladwell made her famous. Yet, these connectors can be essential. As the Chicago Tribune noted , “No Weisberg means, arguably, no Taste of Chicago. No Chicago Blues Festival. No Chicago Gospel Music Festival. No Cows on Parade … No After School Matters, surely the most successful arts-education initiative in the history of the city. No Storefront Theatre. No South Shore Line.”

How can you find and better nurture and support the key players in your organization’s social network?

Organizational Networks Are Hidden Sources of Strategic Success

“Organizational network analysis (ONA)” measures and graphs patterns of collaboration by examining the strength, frequency and nature of interactions between people in those networks.

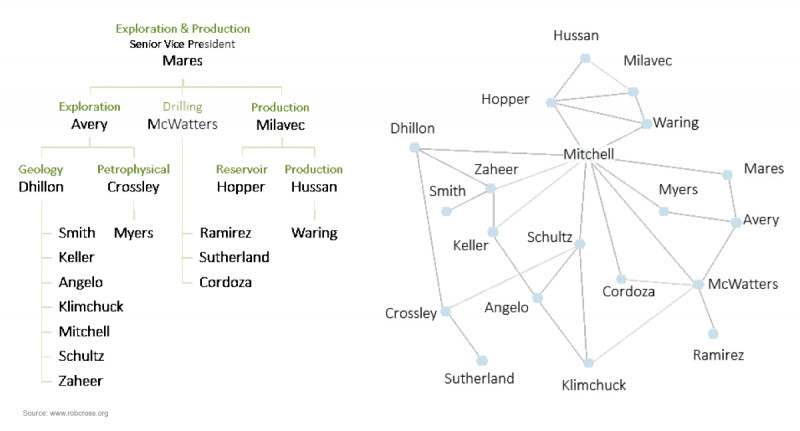

Often, network analysis reveals patterns of communication and influence that are very different from the formal hierarchical structures that leaders rely upon. Here’s an example from Rob Cross’s work , using ONA on the exploration and production division of a large petroleum organization:

This ONA identifies mid-level managers critical to information flow such as the very central role of Mitchell, who is the only point of contact between members of the production division and the rest of the network.

Over two decades of research, Cross and colleagues have found that 3-5% of people in a typical organization network account for 20-35% of the value-adding collaborations. Yet even sophisticated talent management systems tend to overlook about half of these central players.

Among other problems, this means that the people making your most significant collaborative contributions are not getting recognized, and research shows they often burnout and leave. To address this problem, Juniper Networks used ONA to identify “hidden stars” – those that are having a significant impact but being missed by a more traditional performance management system, and relied on those hidden stars to spearhead organizational change.

Use ONA To Amplify Your Traditional People Analytics

Leading organizations increasingly combine network analysis with traditional people analytics for a more holistic talent perspective.

Some use ONA to identify which employees are central and deeply connected to social networks. Then, use people analytics to examine employee grade levels, location, and to identify high potentials. Others use the combination to determine whether their most vital social network connectors are receiving rewards commensurate with their contributions.

Today, ONA reveals not just the number and frequency of connections, but also which people create energy and a sense of purpose. These are ideal succession candidates because, while leaders are typically told that a larger network is better so they maximize social and political activities, recent research shows that this is often the opposite of what drives successful innovation, execution, scale, and well-being. When organizations combine ONA with performance data such as ratings, patent counts, and revenue, they find that high performers are not necessarily those with the largest network, but those whose networks are suited to their personal objectives.

Putting ONA to Work

When it comes to employee engagement and burnout, ONA can identify peripheral network members (like “Sutherland” in the diagram) whose contributions go untapped. Cross’s research shows that in companies with strong cultures, it can take 3-5 years for newcomers to become as connected as high performers. Rapidly forming a network is pivotal to a newcomer’s success, but most organizations offer few blueprints for the kind of network people should build and how to transform a network into success.

At the other extreme, some employees can be too connected, because so many of their colleagues believe others are essential to performance. That sounds good, but those who are too connected often face overwhelming collaborative demands, which leads to burn out and departure. This is often not picked up by traditional engagement surveys or performance systems. Using ONA, HR can help leaders avoid the trap of relying on favorites, expand the network beyond just a few, and reduce the collaborative burden on those that were too connected. Optimizing collaboration networks and practices in this way can retrieve 18-24% of wasted collaborative effort.

Today, ONA reveals not just the number and frequency of connections, but also which people create energy and a sense of purpose.

ONA can also improve employee turnover and retention prediction. Again, many assume that a bigger network leads to better performance and lower turnover, but in fact those with larger networks are often more likely to leave in the first four years. Rather success requires building the right network at the right time .

With this in mind, newcomers should not reach out to as many others as possible. Instead it is being sought out that matters more. More effective newcomers do a lot of exploratory meetings, ask a lot of questions, give away their status rather than exhibit it, and create mutual wins that generate energy. Rather than PUSH, successful newcomers create PULL.

Also contrary to many onboarding programs, the best strategy is not to tie a newcomer to a formal mentor in the traditional hierarchy. Rather, newcomers should connect with the pivotal network connectors, like “Mitchell” in the diagram, which enhances their legitimacy and connections. As employees stay beyond the first 3-4 years, the best ones extend their network further into the organization, which provides a sense of purpose and efficient collaborations .

Furthermore, as organizations strive for greater diversity and inclusion, ONA can measure inclusion beyond simply the number of protected group members, but rather by tracking diverse views at points of influence in collaborative networks. ONA can identify and enhance informal influencers who offer diversity. Bias doesn’t only originate in the six inches between the ears of an individual, but often by the members of their network to whom they listen.

Time to Add ONA to Your HR Toolkit

These ONA-driven strategies tend to require very little additional resources. Often the difference comes down to tracking and encouraging a very small number of pivotal relationships. However, in most organizations, those pivotal relationships are invisible.

Of course we all know from experience–and in our gut–that networks are powerful, just like they were for Lois Weisberg. But to date they have remained invisible and led well-meaning leaders to under-invest in social capital. The time has come for HR leaders to take that knowledge out of their gut and make it an explicit tool for HR leaders and their constituents.

Recognized worldwide for his breakthrough research on the bridge between human capital, talent, and sustainable competitive advantage, John W. Boudreau, Ph.D. is much sought after by organizations, businesses, and the academic world for his insight and innovation in the fields of Human Resources, Human Capital Management, and Executive Development.

Dr. Boudreau is Research Director for USC’s Center for Effective Organizations and Professor of Management and Organization at Marshall School of Business. His large-scale studies and focused field research address the future of the global Human Resources profession, HR measurement and analytics, decision-based HR, executive mobility, HR information systems, and organizational staffing and development.

A strong proponent of corporate/academic partnerships, Dr. Boudreau helped to establish and then directed the Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies (CAHRS) at Cornell University, where he was a professor for more than 20 years.